Introduction to Professional Development

Introduction to Coaching Supervision and Mentor Coaching

Robert Hogan is a well-known personality psychologist and creator of Hogan assessment of personality. He is a firebrand public speaker with a sharp wit and strong opinions. Among his views is the idea that reflection—in an of itself—is insufficient as a mechanism of improvement. Undoubtedly, he would agree that it is better to live the examined rather than the unexamined life. Even so, he believes that introspection has its limits. This is why we need sports coaches, trainers, mentors and other outside influences. Fresh perspectives, challenging points of view, and direct feedback are vital to our development and—importantly—can only be provided externally.

This is the reason that medicine, psychotherapy, coaching and other pursuits have always relied on some form of supervision to help novices transition to mastery. Supervisors provide the safety to reflect, the feedback to improve, and the expertise to guide. Unfortunately, many people who are placed in the role of supervisor have little training in how to effectively develop their supervisees. This manual is intended to be a guide for you to develop supervisory acumen. In the pages that follow, you will be introduced to various models of supervision and to a variety of specific skills that will help you to cultivate small groups of novice coaches and usher them toward responsible independent practice.

Understanding Professional Development

Take a moment and reflect on your understanding of the word “development.” What do you think development is? Is it improvement? Is it growth? Are improvement and growth distinct from one another? Developmental psychologists offer a simple but intriguing set of ways to understand the concept of development.

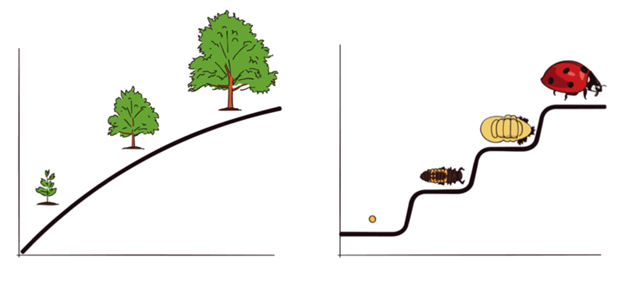

In the first, development is understood to happen in stages. You can see this way of thinking in the idea of childhood versus adolescence versus adulthood. Similarly, you can see an example of this model in coaching certification offered by the International Coach Federation: those with the least experience are Associate Certified Coaches (ACC), while those with more experience and competency are Professional Certified Coaches (PCC), and those at the top of the game with regards to experience and competency are Master Certified Coaches (MCC). This approach is known as “continuous development” and it represents continuous and incremental development over time. To use the metaphor depicted in the illustration, a sapling grows into a young tree that continues to grow into an elder tree.

By contrast, the second approach to understanding development is called “discontinuous.” Instead of gradual change over time, development can occur in radical jumps forward. This is illustrates through the metaphor of the larvae changing in fundamental ways to become a

ladybug. Here, we might see a student coach who struggles with basic competency suddenly “get it” and, seemingly overnight, exhibit a large jump in technical mastery and far more sophisticated thinking about coaching.

In the mentor coaching and coach supervision process, both types of development can occur. We expect continuous development with coaching skills. A person who can ask decent coaching questions can learn to ask better ones, and then still better ones. By the same token, an

important part of coaching development can include radical shifts in the way one thinks about coaching. A person who can shift from the mindset of “coaching is a business I want to develop” to one of “coaching is a service that it is my privilege to provide” has made an enormous leap forward in their understanding of coaching.

Models of Supervision

Understand this: the entire purpose of mentor coaching or of supervision is to promote the best possible service to clients. It may be tempting to think of this process as personal professional development. While it is true that coaches develop through supervision, the ONLY reason to do so is the responsible service of clients. Sure, supervisees might gain confidence or competence, but these are ONLY important in the context of client service. When you—the mentor or supervisor—understand and internalize this simple message, you can better instill it as a professional ethic in those with whom you work. There is simply not a single better focus of professional development than the client. This is about clients, not coaches.

Broadly, you can think of supervision and mentor coaching as a process that is focused on developing novice professionals. Specifically, it is a process that shifts the supervisee from novice to master to independent practitioner. Let’s look at each of the three of these professional milestones:

A) Novice—novices are those who have received training but who currently lack either the student practice or professional expertise to masterfully employ skills. These coaches are still largely “in their heads”; worried about “getting it right” and focused on what to do and how to do it. They tend to be heavily skills focused and can be self-conscious. Novices differ from one another in that some will show promise in some skills but be weak at others and this mix of strengths and weaknesses is unique to each individual learner.

B) Master—Masters are those who have had opportunities to practice skills to the degree that these skills are now second nature. Their facility with skills is high and flexible and they can often work intuitively and spontaneously. People in this stage are often more concerned with modifying or experimenting with basic techniques. They tend to be more concerned with timing— that is, when to best use an intervention—rather than how to use an intervention.

C) Independence—It might seem intuitive that mastery is the highest goal of practice. People who are technically masterful, however, may still be in need of further development. People who are truly ready for independent practice are those who have a firm grounding in ethical decision making, self-care, and continued professional development. Here, the emphasis shifts from a focus on personal skills to the broader notion of professional responsibility and the best possible service to clients. Also note that independent practice does not mean working in a silo. The most responsible coaches regularly check in with peers; seeking out new developments in science, assessment and practice. They attend conferences and join professional societies. Most importantly, they recognize the boundaries of their own independence and are able to seek consultation from peers when necessary.

Supervision and mentor coaching also function by expanding the supervisee’s “cognitive map” of coaching. This is where you are more likely to see discontinuous development in your supervisees. A supervisee who shifts from a naive view that “coaching is positive” to a more sophisticated view that “coaches can potentially cause harm and so bear a responsibility to be ethical, strategic, and professional” has made a radical transformation.

In counseling and psychotherapy, the two human-service professions that most closely resemble coaching, there are a number of widely known and well regarded models of supervision. Some are based on therapeutic orientations (such as Freudian or psychodynamic interactions) and some are based in developmental schemes. Two are worth mentioning here, both because they are well regarded and because they are appropriate to the development of novice and experienced coaches.

The first is a model created by Stoltenberg and colleagues in the 1980s. This model is called the Integrated Developmental Model, and it uses stages to describe supervisees. This model posits the idea that there are three levels of supervisee, each with unique and identifiable characteristics:

Level One: These are novices. They are highly motivated and want to “get it right.” They tend to be highly anxious and are apprehensive about being evaluated. This model recommends that supervisors working with people at this level establish safety, are supportive, and more prescriptive.

Level Two: These are mid-level practitioners. They have some experience but the wrestle with occasional doubt and lack of motivation. This model recommends that supervisors working with people at this level offer opportunities for autonomy, voice, and self-expression.

Level Three: These are stable, secure practitioners. They engage in skilled practice, empathy, and self-care. This models recommends that supervisors working with people at this level treat them with autonomy and offer professional challenge as well.

| STAGE | CONCERNS AT THIS STAGE |

| Level 1: Novices & Students | Getting it right, fear of evaluation, basic competency, acquiring clients |

| Level 2: Mid-level, experienced practitioners | Fluctuating motivation, creating unique brand and presence, professional identity |

| Level 3: Stable, secure, autonomous practitioners | The reputation of the profession, self-care, exceptional client service |

Perhaps the best-known model of supervision is that created by Ronnestad and Skovholt. These collaborators created their approach to supervision by analyzing data collected from practitioners of widely different backgrounds. It is one of the few models that is empirically derived. This model uses “phases” to describe stages of practice, each of which are self-explanatory in their titles:

Phase One: Lay Helper

Phase Two: Beginning Student

Phase Three: Advanced Student

Phase Four: Novice Professional

Phase Five: Experienced Professional

Phase Six: Senior Professional

Importantly, Ronnestad and Skovholt also identified themes that are vital to the professional development process. Here are some that I view as the most relevant to coaching:

- The integration of professional identity and personal identity

- Continuous reflection is a critical feature of professional development

- A lifelong commitment to learn motivates the process of professional development

- Beginners rely on external influence while master rely on more internal influence

- Clients are a major influence on professional development and interactions with clients are seen as learning opportunities

- There is an appreciation that personal life influences professional life

- Effective service is built on an appreciation and acceptance of human variability

Taken together, these ideas and models can help you to be a better mentor coach or supervisor. These models offer easy to remember categories that will help you better understand your supervisees and how best to interact with them. In addition, they offer the guiding tenets around which you can acculturate novice coaches. I summarize them here:

- Coach development is motivated by and in the service of clients. While there may be fringe benefits such as increased coach confidence these benefits are only important to the extent that they translate to the best possible service for clients.

- Coach development is an on-going and life-long process of reflection, feedback, and learning.

- The personal and professional are inherently linked. Coaches who experience personal life distress (eg. a divorce) are less likely to engage in self-care, act ethically, or offer top service to clients. Coaches have an obligation to maintain health and mental health for their clients, or to (temporarily) discontinue service until that can maintain health.