The Benefits of Procrastination

By Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener

Procrastination has long been vilified as an unhelpful and unpleasant human tendency. What if we are wrong?

I’ll quit procrastinating tomorrow

Procrastination. You know it well. Regardless of your background, you have—from time to time—put off large or unpleasant activities: Paying your taxes, making a difficult phone call, turning in an assignment in school, breaking up, going to the gym. The list goes on and on and on, much in the same way that procrastination does.

Procrastination is an interesting example of human behavior that appears to fly in the face of evolutionary theory. Think about it: most human behaviors remain in our collective repertoire because they confer some advantage. For example, smiling and frowning are helpful social signals, telling other people about our internal state. Complimenting, flirting, joking, hugging, cooking, and cleaning; all behaviors with a clear benefit. Even indulging in sweets or drinking alcohol are clearly attractive in the short-term. So, what’s going on with procrastination? Why do we all do it?

The causes and consequences of procrastination

To better understand procrastination, let’s look at results from research on the topic and square these with personal experience. Let’s begin with your own experience. It makes intuitive sense that we put off tasks that are large or unpleasant. No one wants to deep-clean the bathroom or get their teeth cleaned at the dentist. Sure, we can all appreciate that these are important and valuable, but they are not, in themselves, pleasant. So, it makes sense that we tend to put them on the back burner.

It is tempting, therefore, to think that procrastination is sensible except that it is not. Researchers have discovered that people also put off enjoyable and pleasant activities. Remember that gift card you received for your birthday? Why haven’t you cashed it in yet? Have you been meaning to see the amazing landmarks in your area but just haven’t gotten around to it yet? Have your friends told you about a book, a movie, or a play that you are sure to enjoy, but you haven’t yet lifted a finger? People’s ability to procrastinate is almost a superpower.

Procrastination boils down to delaying work on tasks that require time and effort. In essence, we generally prefer to invest time and effort in short-term, smaller projects than we do on longer-term and larger projects. For example, most New Yorkers would like to spend an afternoon at the Museum of Natural History. They know it would be educational and enjoyable. Ask any New Yorker, however, and they might claim “not to have the time.” The effort of breaking out of their daily routine feels prohibitive. Add to this any unpleasantness in an activity—paying a lawyer to write your will, for example—and we are even more likely to put the task off.

Researchers have identified a list of variables associated with procrastination. We tend to avoid or delay tasks that we perceive as meaningless, too difficult, too unpleasant, or require too much time. The real problem is that procrastination is often associated with problems. By putting things off, they don’t get done. Students who procrastinate get lower grades. People who delay “getting into shape” are less healthy, and folks who avoid having a difficult conversation with friends or romantic partners often delay fixing the problem.

What’s more, procrastination itself is emotionally unpleasant. Think about how you have felt when you have put off doing something. If you are like most people, you experienced some combination of guilt, overwhelm, apprehension, worry, fear, and frustration. That is a pretty potent cocktail. In fact, the longer you procrastinate, the more these feelings mount. One theory suggests that it is the increasing volume of these distressing emotions that eventually kick people into gear and get them to begin working, except, of course, that these feelings sometimes lead to paralysis, substandard performance, poor decision making, and hopelessness.

Except when they don’t.

Passive versus active procrastination

Here, at last, we have arrived at the reason you are reading this article: the benefits of procrastination. To appreciate these benefits, it will help you know that procrastination comes in different flavors. Researchers distinguish between “passive” and “active” procrastination. Passive procrastinators are exactly what you think of when you think of this topic: they drag their feet, do work at the last minute, worry a lot, can feel dejected, and generally have lower performance. Active procrastinators, by contrast, do work at the last minute but generally have high performance. In fact, active procrastinators perform just like folks who don’t procrastinate at all!

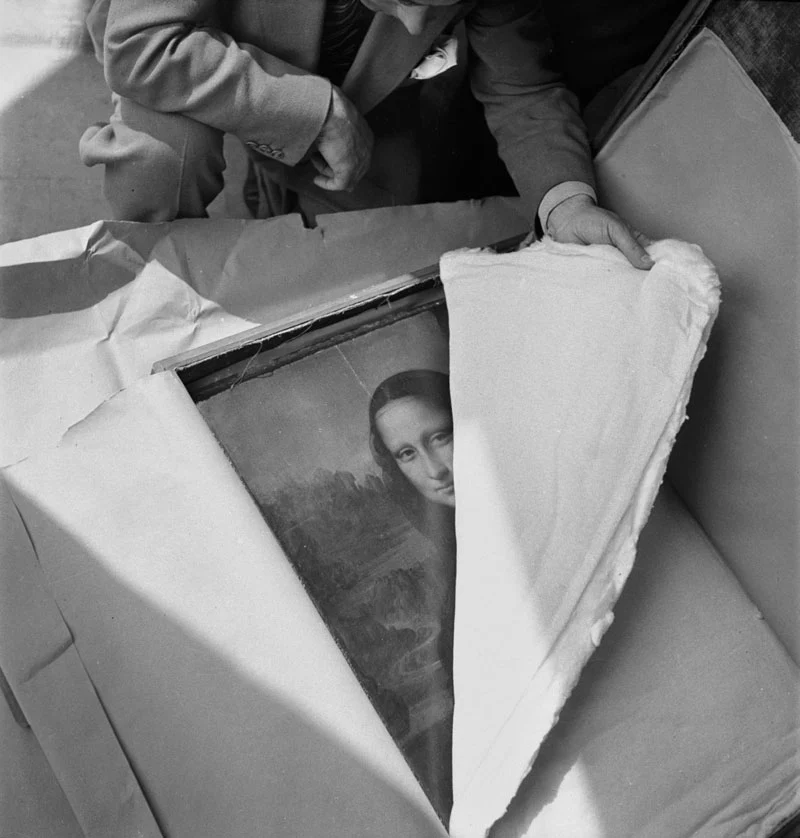

Let me give you a personal example: I almost always do my work at the last minute. If you were to show up at my home office and observe my workday, you might be appalled. You would see me begin the day with an hour or two of drawing—Yep, pencil sketching that has nothing whatsoever to do with my professional life. You might also see me listening to podcasts, knocking off “work” to go rock climbing, or simply sitting in the yard. If you were working on a project with me, your anxiety would likely be mounting as the deadlines drew ever closer. Then, at the eleventh hour—whether that is a few days or a few hours—you would see me suddenly sit up and start working. I would execute high-quality work in a fraction of the time you might think it would take, and it would all be completed exactly on time. I call this “incubation.” Incubators tend to put things off toward the last minute but are, below the surface, thinking about the task all along the way.

The architecture of incubation

What, exactly, sets people like me—incubators (or “active procrastinators”) — apart? The research is clear: incubators differ from classic (or “passive”) procrastinators in some essential ways. Classic procrastinators often lack a belief in their own abilities. They feel they are not up to the challenge at hand. Incubators, by contrast, have high (but accurate) self-efficacy. They tend to be improvisational and good at in-the-moment problem-solving.

Another difference is in the sense of control. Specifically, procrastinators tend not to feel that they control their own time while incubators feel like they are. To put it another way, so-called procrastination is a conscious choice for incubators. When I draw or rock climb, I am deciding exactly how I want to spend my time, and I know that I am choosing to do my work closer to the deadline.

Perhaps the most significant difference between various natural workstyles is to be found in people’s emotional experiences. People differ markedly in their relationship to anxiety. That buzz of stress and worry feels overwhelming to some while it is energizing to others. For example, think of an emergency room doctor who uses life-or-death circumstances to sharpen her performance versus the college student who falls apart in anticipation of the final exam. Incubators are more like that doctor. They thrive on the stresses created by external expectations and tight deadlines.

In fact, by allowing deadlines to motivate, incubators don’t spend much energy on motivating themselves. In fact, this can be part of why it seems that incubators are so carefree and easygoing about work. They aren’t engaged in an internal civil war where the powers of self-control rage against short-term desires. Indeed, multiple studies confirm exactly this point: active procrastinators generally enjoy high levels of wellbeing. Their natural way of working is associated with higher rates of autonomy and mastery than is classic procrastination.

Find your flow

Among the interesting aspects of active procrastination is its relation to flow. If you are not familiar with flow, then here it is in a nutshell: flow is a state of total absorption in which you lose track of time and lose a sense of self. People call it “being in the zone.” Flow states happen when there is an optimal match between a person’s skill and the challenge before her. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, the psychologist who pioneered the concept, is both a chess player and a rock climber. Notably, both chess and climbing have formal rating systems for difficulty so that it is easy for enthusiasts of both activities to match their skill to a particular challenge and get into flow.

Although flow is remembered as a euphoric state, too much challenge can be frustrating or anxiety-provoking, and too little can be boring. You will observe that procrastination is a behavior that we can examine through the lens of flow. Procrastinators often feel anxious because they view the task’s challenge before them as overwhelming to their own skills and abilities.

Enter incubation: active procrastinators engineer flow states by putting off work until the last minute. By delaying work, they turn up the volume on challenge. They continue to do so right up to the point that they intuitively feel that optimal difficulty level. Depending on the specific task, this might be days or just hours before the deadline. Sure, they might tolerate some anxiety knowing that they are going to be working under intense pressure, but the higher stakes also tend to sharpen their focus and put them into flow and improve their performance.

The eleventh hour

When I tell people about incubators and about active procrastination, they react positively. Some of them feel like I have written a permission slip for classic procrastination. I have done nothing of the kind. Procrastination is still just procrastination, and everyone does it from time to time.

If you are a procrastinator, there are encouraging lessons for you. Delaying work is a signal. Your behavior reveals your attitude about the task at hand. It suggests that you find it overwhelming, unpleasant, or too committing of time or other resources. Fortunately, there are remedies for all of these problems. Overwhelm can be addressed through baby steps or collaboration. Unpleasantness can be managed by “eating the frog”—simply jumping in and tackling the tasks in the same way that you jump into the deep end of a cold swimming pool. Time and resource commitments, similarly, can be addressed through careful scheduling. Rather than setting yourself up for poor performance and guilt, try to diagnose your problem and treat it accordingly.

Other people react to the concept of active procrastination with relief. They finally quit beating themselves up for a natural and effective work style. Having a label, a language, and an understanding of their tendencies can be empowering.

If you are an incubator, the take-home messages for you are twofold: first, let yourself off the hook. You are actually working effectively, even if others cannot see it. Secondly, it is your responsibility to educate those you work with about your unique style. You cannot expect them to trust you automatically. Be transparent about your process, listen to their concerns, and build trust over time.

About the author

Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener

Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener is passionate about leaving the research laboratory and working in the field. His studies have taken him to such far-flung places as Greenland, India, Kenya, and Israel. He is a leading authority on strengths, culture, courage, and happiness and is known for his pioneering work in the application of positive psychology to coaching.

Robert has authored more than 75 peer-reviewed academic articles and chapters, four of which are “citation classics” (cited more than 1,000 times each). Dr. Biswas-Diener has authored nine books, including the 2007 PROSE Award winner, Happiness, the New York Times Best Seller, The Upside of Your Dark Side, the 2023 coaching book Positive Provocation, and Radical Listening, in 2025.

Thinkers50 named Robert to be among the 50 most influential executive coaches in the world.

Robert Biswas-Diener

Get updates and exclusive resources