The Psychologically Rich Life

By Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener

Some people think happiness is pleasure. Others think that it is meaning. What if it is something else?

Introduction: Psychological Wealth

In 2007, my father and I had a bit of good luck. We were collaborating on a book that would review all of the major findings from the science of happiness. The book did well and won the 2008 Prose Award for the best title in psychology. What’s more, it was published just as the financial crisis hit. A core message of our book suddenly felt timely: psychological wealth is more important than material wealth. In our book, we suggested that happiness involved fulfillment in many areas: meaningful work, health, financial security, spiritual connection, and having a positive attitude. We argued that if a person invested in developing each of these areas, she would be resilient against a problem in any one area. Even the psychological hardship of the financial crisis, for instance, could be mitigated by wins in health, work, or friendships.

Ours was only a single example of the ways that well-being experts have framed life’s most sought-after experience. For years, policymakers, interventionists, and researchers have offered simple frameworks for understanding and increasing happiness. You might be familiar with those associated with positive psychology research, such as Marty Seligman’s PERMA approach or Carol Ryff’s psychological well-being. You might be less familiar with more widely implemented approaches such as the Future Generations Act in Wales. Wales is the only country to have legislated leaving the world a better place for future generations. I have seen this initiative up close because I serve on a global council with the Welsh Commissioner, Sophie Howe. I have been inspired to see how she advocates for well-being, broadly defined in policies related to transportation, job creation, preserving Welsh culture, and other national initiatives. I also count myself lucky to be associated with Nancy Hey, the executive director of the What Works Centre for Wellbeing. Nancy’s initiatives roll out across the UK and are aimed at collecting data on important issues such as loneliness and the global pandemic. In addition, the Centre has identified several strategies that increase happiness, including:

- Programs to support physical activity and healthy eating

- Providing financial advice and support for retirees

- Programs that create opportunities to volunteer

- Social prescribing, in which healthcare patients are connected with community support and social events as part of treatment

I like this list because it differs from the individualistic happiness strategies we so often see associated with positive psychology. Sure, cultivating gratitude and adopting a daily mindfulness practice are reasonable methods for increasing your own happiness. Even so, they are not policy tools and offer little for those of us who would like to positively impact well-being at scale and especially among people from disadvantaged backgrounds. In essence, we seek to increase psychological wealth.

In this post, I will discuss a new program of research on happiness. For those who are frequent consumers of ideas emerging from positive psychology, I hope to offer an intriguing new approach to understanding happiness for your consideration.

This, that, and the other: 3 approaches to the good life

Over the last two decades, it has become fashionable to speak of happiness as if it comes in two distinct flavors. Those who have championed this division have drawn heavily from Hellenistic Greek philosophy to devise their categories. On the one hand, is “hedonic well-being,” which, as the name implies, emphasizes pleasure. If you want a more sophisticated understanding of hedonic well-being, you could think of it as an amalgam of stability, comfort, and pleasantness. The good life, by this definition, would be somewhat predictable, in which there is material and psychological security, and in which there are enjoyable activities.

On the other hand, there is “eudemonic well-being.” This name, drawn from the writings of Aristotle, suggests that there is more to the good life than just feeling good. Various researchers have offered elements of eudemonic well-being: flow states, personal expressiveness, autonomy, growth, and meaning in life, to name a few. As an approach to research, having so many variables is not advisable. To simplify our understanding of eudaimonia, you can think of the good life as being one that is purposeful, coherent, and significant. In this case, a person would feel that what she does makes sense, has opportunity for impact, and is important.

If you keep up with writing in positive psychology, these two approaches are likely familiar to you. You may be less familiar with a third approach to understanding the good life: the psychologically rich life. Simply put, the rich life is one in which a person experiences a variety of interesting activities that have the potential to shift one’s perspective. Did you get all that? The rich life differs from the happy life in that the activities are perspective-changing rather than just enjoyable. The rich life also differs from the meaningful life in that the activities are varied. Shige Oishi, the researcher at the helm of this program of study, thinks that the rich life is characterized by variety, interest, drama, story, and emotion.

I am attracted to this notion of the good life, in part, because it allows for the experience of unpleasant as well as pleasant times. For example, as a child, I was once stuck in an elevator with my father in Italy. Once, on a layover in Los Angeles, I met a friend and swam a mile in the Pacific before boarding my next flight. Once, I found a 20-dollar bill in a book used as a decoration on the wall of a restaurant. Once, I worked as a crew member on a long-distance horse race. None of these experiences were about pleasure and comfort; nor were they steeped in meaning, growth, or purpose. Each of them, however, was a standout experience. Each is something I have told in story form and which I call to mind as a discrete episode in my life worth remembering.

The rich life ledger: An accounting of the research

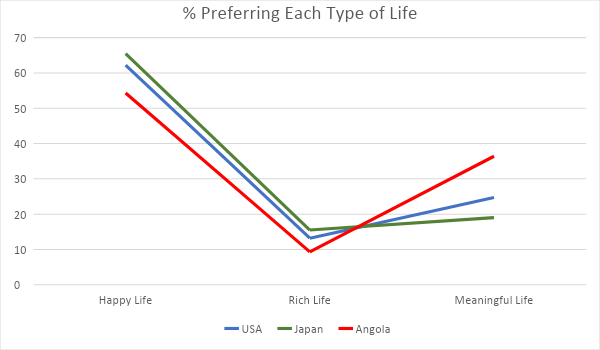

The Oishi research team has already published several studies of this delicious new approach to the good life. In one such study, they recruited nearly four thousand participants from nine nations to choose between the happy life, the meaningful life, or the rich life. Take a moment and consider your own preference. It turns out that the majority of people—between 50 and 70%, depending on the country—wanted the happy life. That’s right, people prefer stability, comfort, and enjoyment. Next in line was the meaningful life. In this instance, between 14 and 40% of the respondents preferred meaning. Finally, between 7 and 17% of the participants preferred the rich life. This makes sense: too much novelty, variety, and drama would be difficult to endure.

In another study, the Oishi research team evaluated a number of the correlates of the rich life. Regarding personality, they found a moderate relationship between extroversion and openness to experience (respectively) and the rich life. They also found that there is a relationship between positive emotion and a very small relationship to life satisfaction.

These broad findings are interesting, but they provide little insight into what the rich life actually looks like. Fortunately, the research team used a number of “daily diary” studies to investigate exactly this question. They looked at a number of everyday activities to see which were most associated with the rich life. When they evaluated playing video games, taking a short trip, and religious activities, they found that only taking short trips had an effect. This makes sense: many day trips are neither steeped in meaning nor are they predictable or comfortable. They do, however, tend to be novel and interesting. Oishi and his colleagues followed up this lead to discover that college students who study abroad report a larger increase in the richness of their lives across the semester than do their counterparts who stayed home. This finding held true among Chinese students studying in the USA as well as for American students who went abroad.

The idea that a day trip constitutes a happiness intervention is an interesting one. First, it differs from the “choose happiness” mental interventions that are so common in positive psychology. In addition, it is a relatively modest and attainable activity. It is not about jetting off to Paris or Hawaii. It might be as achievable as a picnic in a local park or a jaunt to a nearby beach. It is here, also, that social class once again rears its head. Having a little disposable income and some time affluence appears to position people for a psychologically richer life. Looking at my own examples—traveling to Italy, swimming in Malibu, traveling to the forest for a horse race—all seem very middle class upon reflection. This is yet another argument in favor of addressing inequalities that allow some people greater access to novel and perspective-changing activities.

Conclusion

This relatively new line of research can invigorate discussions of the good life and help you think about your own happiness. You can think of your happiness as a three-legged stool upon which to sit: the experience of pleasure, meaning, and richness. You likely do not need them in equal proportion, nor do you necessarily need all of them in a single day. Over time, however, it will feel fulfilling to attend to all three dimensions of the good life. Ask yourself, “what can I do that will be enjoyable?” “what can I do that will feel like it matters?” and “what can I do that will give me a fresh perspective?”

About the author

Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener

Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener is passionate about leaving the research laboratory and working in the field. His studies have taken him to such far-flung places as Greenland, India, Kenya, and Israel. He is a leading authority on strengths, culture, courage, and happiness and is known for his pioneering work in the application of positive psychology to coaching.

Robert has authored more than 75 peer-reviewed academic articles and chapters, four of which are “citation classics” (cited more than 1,000 times each). Dr. Biswas-Diener has authored nine books, including the 2007 PROSE Award winner, Happiness, the New York Times Best Seller, The Upside of Your Dark Side, the 2023 coaching book Positive Provocation, and Radical Listening, in 2025.

Thinkers50 named Robert to be among the 50 most influential executive coaches in the world.

Robert Biswas-Diener

Get updates and exclusive resources