The Modern History of Happiness Research

By Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener

The story of Positive Psychology is more than Aristotle, Maslow, and Seligman

Introduction

As any textbook author can tell you, summarizing an entire field is a difficult task. Imagine, for example, writing about the “history of medicine.” It would include the philosopher-physicians of antiquity, non-Western approaches to medicine, the advent of surgery, the development of medicines, the creation of hospitals, breakthroughs in genetics, and many other topics. The same is true of positive psychology. It is more than the simple story that is often told: positive psychology rose in the late 1990s and is a growing sub-discipline of psychology. Here, I will take just a single concept—happiness—and trace some of its research history in modern psychology.

What is "Modern Psychology?"

We could argue about when psychology became “modern” but, for our purposes here, let’s just tag it to the period in which people were attempting to give serious, systematic attention to psychological phenomena. This places us in the 17 and 1800s. A period that historian Morton Hunt, describes as “physicalist.” This is when medical doctors were sending jolts of electricity through the nervous systems of dead frogs, measuring the sensitivity of human skin, and paying attention to the ways that brain lesions affect thinking.

It was a time when researchers were creating new scientific methods even as they were studying their topics of interest. For instance, Francis Galton (eugenicist and Darwin’s cousin), was interested in studying intelligence. To do so, he systematically studied people’s ability to estimate distance and he pioneered the use of twins to study genetics. He developed the statistical concept of correlation. These studies provided the foundation for our modern science in that they suggested that psychological topics could, indeed, be researched.

This all culminated in the late 1800s with the rise of the figures (all men, although Mary Whiton Calkins is a noteworthy exception) who we associate with the advent of modern psychology:

- Wilhelm Wundt (founder of the first formal laboratory for psychological research as well as the first journal in the field)

- G Stanley Hall (founder of the first English language psychology journal and was first president of the American Psychological Association)

Happiness was a topic of research interest in the early decades of the 1900s. Researchers employed self-ratings of happiness as early as 1930. It was the age of behaviorism, and researchers wanted to see what happy people did. They were especially interested in marriage, education, and work as influences on a person’s happiness. This reveals the prevailing assumptions about happiness at the time: that it is a state of wellbeing that results from having favorable life conditions. It is a sensible thought.

Happiness Research Gets Mentalized

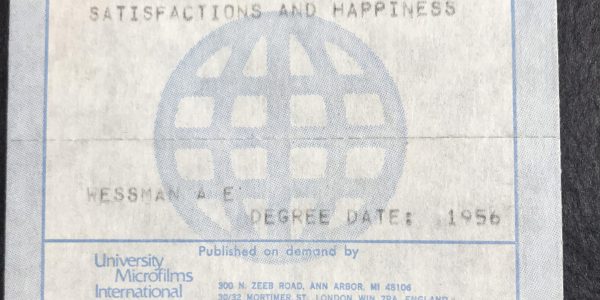

In 1956, Alden Wessman, a student at Princeton, handed in his doctoral dissertation: A psychological inquiry into satisfactions and happiness. I mention this because Wessman’s 250+ page manuscript could only be written if there was a substantive body of research for him to discuss. Indeed, he cites large studies of “national morale” as well as research on avowed happiness across the lifespan. There are discussions on the nature of positive and negative emotions, the concept of life satisfaction, and the role of interest in happiness.

Interests and wants, were important elements of understanding happiness during that period. Edward Thorndike had spent the previous decades writing about these topics and their primacy in happiness studies represented a subtle shift. While the predominant approach to research was to link happiness to life circumstances, a new school was treating happiness as a mental phenomenon. Could it be, for example, that a person’s wants and desires affected their level of happiness? Might ambition help give rise to personal meaning? Or, counter to that notion, could ambition backfire and reduce a person’s satisfaction? These questions marked the advent of mentalizing happiness.

Behaviorism was waning, and new schools were finding purchase to offer alternative theories, new methods, and new data. They were increasingly interested in motivation, emotion, and cognition. It was during this exciting new time that the humanists, such as Abraham Maslow, and the social psychologist Norman Bradburn weighed in on wellbeing. Bradburn, in particular, was keen to chart the territory. In fact, he considered understanding the nature of happiness as important as understanding the correlates of happiness. He mentalized happiness and was interested in how novelty, adaptation, and other psychological processes might be linked to wellbeing.

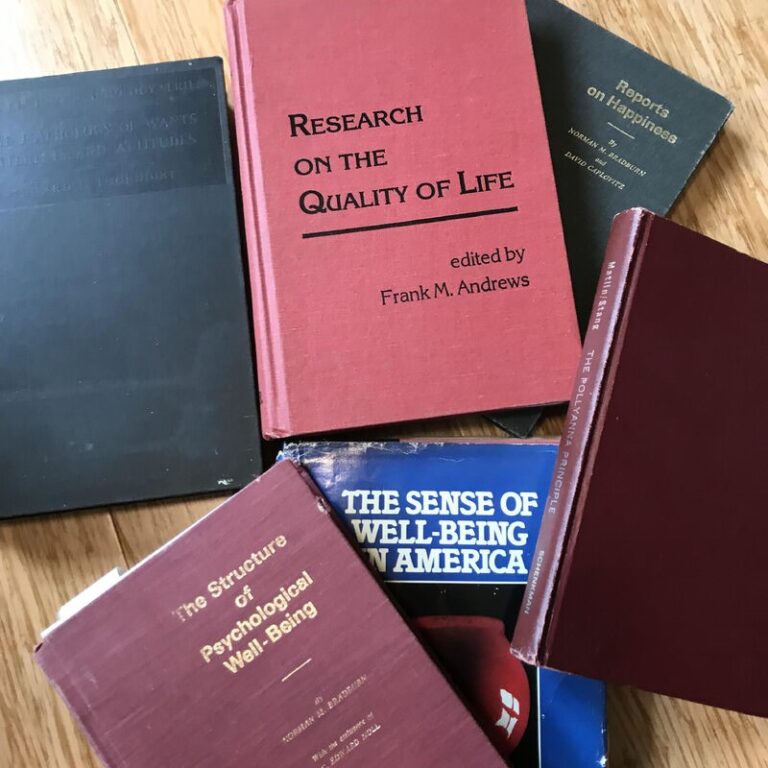

In his masterwork, the Structure of Psychological Wellbeing, Bradburn complains that scientific psychology is too often split between “hedgehogs” and “foxes.” The first group wants to create sweeping theories to explain everything and the second group gets mired in parsing concepts apart to understand their inner workings. Bradburn hoped to bridge the two schools of thought.

He wanted to study the phenomenon of happiness but not just to see what caused it or correlated with it. Instead, he wanted to understand the experience of it. To this end, he focused on positive and negative emotions, which he viewed as core to the experience of happiness. He found that they were independent of one another, meaning that happiness could be improved both by reducing negative experiences and boosting positive ones.

The 1970s

The 1970s marked few advances in happiness studies, although there were notable publications. Of these, Michael Fordyce’s creation of happiness interventions stands out. Fordyce encouraged people to engage in the kinds of behaviors that happy people engage in: worry less, be more outgoing, plan, and be optimistic—to name just a few. Fordyce was the first, as far as I know, to formally test happiness interventions using experimental and control groups.

The other landmark publication from this decade is Margaret Matlin and David Stang’s The Pollyanna Principle. Published in 1978, this book was (in my opinion) the most thorough exploration of the psychology of happiness at the time. It was, I know, a major influence on my father. Even 50 years later, this is a book of impressive insight. Matlin and Stang offered a research-based look into the inner workings of happiness judgments. They examined the role of positivity biases in memory, the ways that people use salient positive and negative information when evaluating the quality of their lives, the use of language, and the role of perception in happiness.

Perhaps more than any other authors up to that point, they distinguished the scientific approach to understanding happiness as being non-religious, non-philosophical, and non-theoretical. Those other accounts often focused on wellbeing as it relates to causes, character, and values. Matlin and Stang, by contrast, described the experience of happiness as a collection of interrelated psychological processes (attention, perception, judgment, and memory). Despite these advances, the study of happiness in the 1960s and 70s was considered a fringe focus.

The Night Before Positive Psychology

I like to think of the 1980s and 1990s as “the night before positive psychology,” which was formally launched in 1998. These two decades were a turning point in the study of happiness, largely because three highly productive scientists devoted their careers to the topic: Ruut Veenhoven, Ed Diener, and Carol Ryff.

- Veenhoven: Ruut, a sociologist, began publishing on wellbeing in the late 1970s. He was primarily interested in using large surveys to track average levels of happiness across groups and across time. He also pioneered the idea of a “happy life year;” in which he calculates how well a nation is faring by looking at how long people live within the context of how happy they are during those years. Ruut later created the World Database of Happiness, which collates more than 16 thousand publications on the topic.

- Ed Diener: In 1984, Diener authored the seminal article in the field of “subjective wellbeing.” In some ways, his attention to the subjective aspects of happiness was a direct offshoot of Norman Bradburn’s work. Diener added a cognitive dimension—life satisfaction—to Bradburn’s measures of emotion. From there, Diener spent decades examining every aspect of SWB: cultural influences, personality influences, adapting to life circumstances, the health benefits of happiness, and many more. Because Diener was a highly-regarded social psychologist, his program of research helped to legitimize happiness as a serious scientific topic.

- Carol Ryff: Publishing in the late 1980s, Ryff’s work on happiness was groundbreaking. She differed from Bradburn and Diener in her approach to wellbeing. Carol rightly pointed out the lack of theoretical underpinnings in happiness research. For example, she highlighted Erikson’s well-known stages of development in which people at each age of life contend with predictable psychological gymnastics related to identity and impact. For Ryff, the idea that a person was functioning well meant that they were successfully engaged in a variety of basic psychological processes such as self-acceptance, experiencing autonomy, and enjoying personal growth. Her theory-oriented approach was indicative of the fact that wellbeing studies was finally established enough to have dissenting voices and constructive conversations between researchers.

It may be noteworthy that it was in the context of the 1980s and 90s that my generation of positive psychology researchers cut our professional teeth. People like Sonja Lyubomirsky, Shane Lopez, Barb Fredrickson, Todd Kashdan, and Laura King. We all experienced a pre-positive psychology time when it was still common to hear people describe happiness studies as “a fool’s errand” and “a waste of time.” At the same time, we also had methodologically sophisticated role models and mentors. It was a period when we could speak with one another but it was still difficult to speak about what we did to people outside our field.

Seligman and His Legacy

In 1998, Marty Seligman was elected president of the American Psychological Association and announced positive psychology as his major presidential platform. Although he is known for his pioneering work on the VIA character strengths and the PERMA wellbeing framework, Marty’s greatest contribution to positive psychology has been in installing its infrastructure. He used the first decade of the field to secure research grants, promote a flagship academic journal, create a professional organization, develop a Master’s degree program, create mentorship opportunities for young scholars, and establish regular conferences. In many ways, it is these—and not the various topics of positive psychology—that make up the field.

Positive psychology is now well-established, and whole new generations of people are just now discovering this science. The idea that there is research on happiness is exciting and relieving in equal measure. What’s more, we have to spend considerably less time justifying this research than we did in decades past. In this new, highly supported context, the study of happiness has exploded. The number of journals and journal articles is rising exponentially.

Among the most exciting advances in the field during this period are:

- The consequences of happiness. Instead of asking “What leads to happiness?” researchers have inquired about “What does happiness lead to?” Lyubomirsky, King, and Diener published a landmark review in 2005 and in the two decades since, dozens of studies have examined the health, social, and work benefits of being happy.

- Bigger and better data. In the digital age, we have bigger and better data collection tools. We can perform text analysis of millions of tweets and social media posts, we can use cell phone GPS to correlate happiness with place, and we can engage in more direct experience sampling, in which we are able to see how people feel in the moment, and we are able to look at genetic links to happiness. Methodologically, this is exciting but it also provides new insights in trends, especially those related to collective attitudes, worries, and pleasures.

- Cultural insights. We are ramping up both our cultural and cross-cultural approaches to studying happiness. The former looks at local experiences and the latter compares across cultural approaches. Taken together, these approaches allow us to include more nuanced definitions of happiness while still acknowledging the possibility and usefulness of making group comparisons.

- Eudaimonic and hedonic happiness. Rather than confining the study of happiness to feelings, there is now room to look at a wider assortment of wellbeing: safety (hedonic), meaning (eudaimonic), enjoyment (hedonic), authenticity (eudaimonic), and others. I will mention that I believe it is a mistake to characterize eudaimonic happiness as “real happiness” while dismissing hedonic happiness as superficial. Instead, these processes work together within us and studying both gives us a more complete view of happiness.

In the end, I hope that this brief modern history helps illuminate the fact that positive psychology has been advancing in a logical and piecemeal way over the decades. I also want to acknowledge that there are many researchers that I did not name, largely due to space limitations.

About the author

Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener

Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener is passionate about leaving the research laboratory and working in the field. His studies have taken him to such far-flung places as Greenland, India, Kenya, and Israel. He is a leading authority on strengths, culture, courage, and happiness and is known for his pioneering work in the application of positive psychology to coaching.

Robert has authored more than 75 peer-reviewed academic articles and chapters, four of which are “citation classics” (cited more than 1,000 times each). Dr. Biswas-Diener has authored nine books, including the 2007 PROSE Award winner, Happiness, the New York Times Best Seller, The Upside of Your Dark Side, the 2023 coaching book Positive Provocation, and Radical Listening, in 2025.

Thinkers50 named Robert to be among the 50 most influential executive coaches in the world.

Robert Biswas-Diener

Get updates and exclusive resources