Stand Up!

By Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener

Stand up for what you believe is right. But, don't both sides believe they are right?

Introduction

As a positive psychology researcher, I am always on the lookout for topics that are somewhat overlooked in the field. We know that mindfulness, happiness, resilience, and optimism are mainstays of positive psychology. They are well-researched and clearly represent what goes right, rather than wrong, with people. There are, however, many other less well-known topics that count as positive psychology such as taking initiative, doing a favor, or being hospitable. One of these is standing up for what you believe to be right.

There is no clear consensus on how to label or define this real-world phenomenon. Imagine, for instance, protesting a newly enacted law that appears to discriminate against poor people. Standing up for your values, in this case, is an amalgam of argumentation, values, courage, allyship, a justice orientation, and optimism, to name just a few qualities. Perhaps it is this hard-to-pin-down aspect of this phenomenon that leaves it at the periphery of positive psychological science.

And yet, we all know it. We have done it. We have seen others do it and have felt inspired by it (inspiration being another positive psychology topic that is somewhat overlooked). The classic photograph of the so-called “tank man” blocking the column of tanks during the 1989 protests in Tiananmen Square endures as a cross-cultural symbol of standing up for one’s beliefs.

Part One: We have always done this

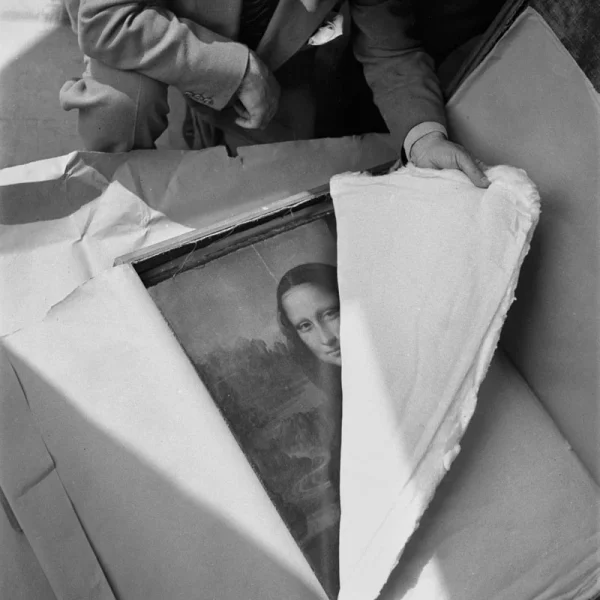

Standing up for what a person believes to be right is universal, existing both across history and culture. Take the lovely example of the village of Chambord, in the Loire Valley of France. During WWII, as the Nazi forces plunged deeper and deeper into France, the staff at the Louvre Museum hatched a plan—operation sauvetage (rescue)—to save important pieces of art, including the Mona Lisa, the winged torso sculpture of the Nike of Samothrace, and the Venus de Milo. In a single night, they unframed, rolled, and evacuated more than 800 paintings.

The resistance organized a convoy to transport the artwork from Paris to Chambord, a place chosen because of its remote location and intact, heavy-walled infrastructure. The crates in which the art was packed were marked with color-coded circles indicating the rarity and value of the contents. The Mona Lisa was marked with three red circles, the highest value possible. I think three red circles might serve nicely as a modern symbol of principled resistance.

The residents of Chambord provided food to the resistance and even, in some cases, evacuated their homes to make room for art and soldiers. Nazi art-hunters, led by Hermann Goring, prowled the country in the hope of confiscating valuable works. They even visited Chambord twice but were unable to capture any notable art. This is in large part due to the way that the French stood up, at great peril to themselves, to protect humanity’s collective treasure. They created decoy artwork. They forged manifests with misleading cargo information. They moved the art from safehouse to safehouse (The Mona Lisa, for example, had 5 separate homes during her exile). The local police never divulged the secret location.

Part Two: But, don’t both sides believe they are right?

One more reason that this topic might be less popular is that it is murky. People on both sides of an issue might equally believe in the moral superiority of their own position. In 2014, for instance, an Islamic militia overran the remote caravan town of Timbuktu, in Mali. They immediately began purging any artifacts that they believed were immoral. This included the destruction of a statue of a Djinn (traditionally the guardian of the town) as well as the burning of more than 4000 manuscripts that were hundreds of years old. Certainly, this group of ideological puritans believed in the moral rightness of their actions.

Although the Al-Qaeda-linked rebels burnt the local library, most of the manuscripts were secreted away by people who had a different view of what is morally correct. In Timbuktu, it is traditional for family members to swear to protect their ancestral manuscripts. These hand-scribed books had been passed down through the generations and represented one of the most complete written collections of West African history, language, religion, and culture.

Together, the residents of Timbuktu transported more than 350 thousand priceless documents away from town, often by boat, donkey, motorcycle, or car. To put that in perspective, if each manuscript were only a single sheet of paper instead of a book, the stack would rise 35 meters (about 120 feet) tall. And, to put that into perspective, that is about as tall as six stacked giraffes or as long as 17 queen-sized beds. So, just imagine trying to smuggle those out of town.

On the one hand, we want to side with the townspeople who save our collective cultural treasures. Yet, it is hard to know exactly what to do with groups who use bigotry, violence, and repression as tools to support their own “standing up for what is right.”

Part Three: What positive psychology has to say about it

Fortunately, this “there-are-two-sides” issue is something that positive psychology researchers have weighed in on. Cyndi Pury, arguably the world’s foremost authority on courage, has mused about so-called “bad courage.” She and her research team read through the letters and manifestos left by people who committed terrorist acts and killing sprees. They were looking for evidence of three distinct concepts that are central to courage:

- Volition—the idea that an action was taken freely and intentionally (88% of the narratives suggested this to be the case)

- Risk—the idea that taking an action was done even in the face of a real risk (62% of the narratives recognized a serious risk)

- Value—the idea that the action was taken in pursuit of a worthwhile goal (a whopping 100% of the narratives believed the action to be correct, citing its potential for positive impact on society or to inspire other, like-minded people)

If you speak with Cyndi about this study, as I have, you quickly realize how unsettling it is and how difficult it was for the members of her lab. To address this difficult issue, Pury distinguishes between two types of courage. The first is “process courage.” Process courage is mostly what you think about when you think of bravery. It is the capacity to take action, despite a risk, in order to accomplish something worthwhile. The person performing the action is the judge of the relative merits of process courage.

“Accolade courage,” by contrast, is determined by observers. It is, in a way, a democratic form of courage in which other people “vote” by judging whether an action is noble. When we award medals of valor to wartime heroes, this is an instance of accolade courage. There are awards for helping Jews in WWII, for courage in the arts, for courageous women, for medical doctors who take risks, and dozens of others. More than anything, it is the idea that people don’t get to be the final word in judging their own actions.

The American historian Sarah Vowell bridges this divide nicely when she argues for the right of all people, not just some people, to protest: “Freedom of expression truly exists only when a society’s most repugnant nitwits are allowed to spew their nonsense in public.” Let them voice their toxic views, she seems to suggest, and we will let the whole of humanity, sometimes in the form of history, decide whose point of view has the most merit.

I want to be clear, however, that I do not believe that Sarah would advocate the violence sometimes perpetuated by religious extremists. I am pretty confident that she feels similar to the way that you and I feel: it is okay for everyone to have a point of view, but instigating violence is rarely the sign of a morally evolved position. As Abraham Lincoln put it in his Second Inaugural address, delivered in the middle of the Civil War: one side “would make war rather than let the nation survive; and the other would accept war rather than let it perish.”

Conclusion

Positive psychology is the science of people when we are at our best and standing up to injustice, sticking up for an underdog, and protecting valuable objects and ideas are all part of our being at our best. We live at a time where championing others, voicing outrage, and standing up are vitally important.

If you want a deeper dive on the topic of principled rebellion, check out Todd Kashdan’s book, The Art of Insubordination, or his blog Provoked.

Get updates and exclusive resources

About the author

Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener

Dr. Robert Biswas-Diener is passionate about leaving the research laboratory and working in the field. His studies have taken him to such far-flung places as Greenland, India, Kenya, and Israel. He is a leading authority on strengths, culture, courage, and happiness and is known for his pioneering work in the application of positive psychology to coaching.

Robert has authored more than 75 peer-reviewed academic articles and chapters, four of which are “citation classics” (cited more than 1,000 times each). Dr. Biswas-Diener has authored nine books, including the 2007 PROSE Award winner, Happiness, the New York Times Best Seller, The Upside of Your Dark Side, the 2023 coaching book Positive Provocation, and Radical Listening, in 2025.

Thinkers50 named Robert to be among the 50 most influential executive coaches in the world.